|

| In the basement of the Melmont Schoolhouse |

Last weekend, my daughter and I visited Melmont, Washington, an abandoned coal-mining town midway through the Carbon River's descent off Mt. Rainier. Melmont disappeared from maps in the early 1920s. During its 20 active years, it produced coal for the Northern Pacific Railway. After the railway switched from steam to electric and diesel, the town whithered and died.

To reach the Melmont townsite, Kay and I parked at a turnout close to the Fairfax bridge on SR-165. From there, we descended the embankment, using the bridge piers for support. 30 feet down we met the now-untracked Northern Pacific Railway grade and began walking.

|

| Fairfax Bridge |

A few minutes in, we passed the unroofed walls of the dynamite shed, which, as the name suggests, stored explosives. Nearby, we saw what I first thought was a retaining wall for the railway grade. It was three feet high on one side and twelve on the other, thick, and made of stone. Later, I read that the wall may have been part of the tipple, a structure used for filling train cars with coal.

Here and there, we paused to pluck the bland yellow salmonberries that drooped from the vines. At least once, stinging nettles seared my offending hand.

A mile on, the townsite appeared below the grade. Now a grassy meadow, small else suggests its peopled past but the collapsed remains of an old truck.

|

| The dynamite shed, located a safe half-mile or so from the townsite |

On Christmas Eve of 1905, Melmont Mine foreman, Jack Wilson, and his daughter were asleep at home when a load of dynamite exploded beneath their floorboards. All the windows of the house blew out, but Wilson and his daughter emerged unharmed. A miner named David Steele was charged with the bombing. He was later acquitted for lack of evidence. I haven't found anything suggesting Steele's motive, though given Wilson's position as foreman, it seems likely that the conflict was work-related and his daughter (age unknown) incidental.

|

| An old truck |

After lunch, we left the main townsite, went back to the railroad grade, and ascended a small path ending in a second clearing.

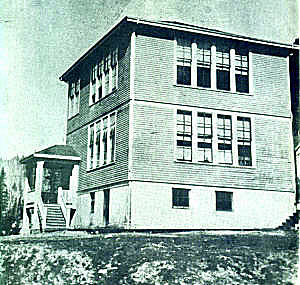

Only the stone foundation of Melmont School remains. We stepped inside, amid full-grown trees and bramble. I showed Kay a photo of the school as it once was. She tried to decide which part of its footprint the students sat above. I studied the knee-high remnants of internal walls. The basement had been divided into separate rooms.

Melmont's last resident, a man named Andrew Montleon, lived in this very basement after fire ate most of the town's deserted buildings. I have not found anything suggesting why Montleon stayed in Melmont or how he supported himself once the town was gone. Did he have an income stream, or did he simply live off the land? Perhaps he was a trapper, a forager, or did something with wood. Maybe he had found some way to scavenge occasional pennies from the town remains and dead mine.

I wondered what had compelled Montleon to stay in Melmont after everyone else had left town. Was he committed to the land (or simply stubborn) like old Harry Truman whose body now lies yards beneath the ash of Mt. St. Helens? Did he think the world beyond simply had nothing to offer and he'd rather while life away in the only place he knew? Or maybe he was paralyzed in some unseen and visceral way, depleted, unable to summon the sense of purpose to do more than resist the tides of time.

Of course, it's easy to project eccentricities on someone we know only through stories of a single action or choice. After all, Montleon may have had good reason to stay in Melmont, and, given circumstances we will probably never know, doing so may have been his only option.

|

| Melmont School in better days (from ghosttownsofwashington.com) |

No comments:

Post a Comment